czwartek, 26 czerwca 2008

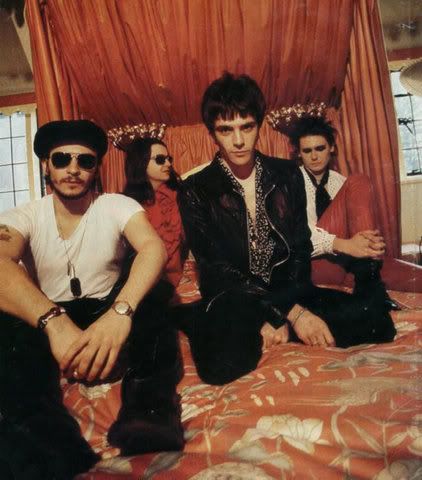

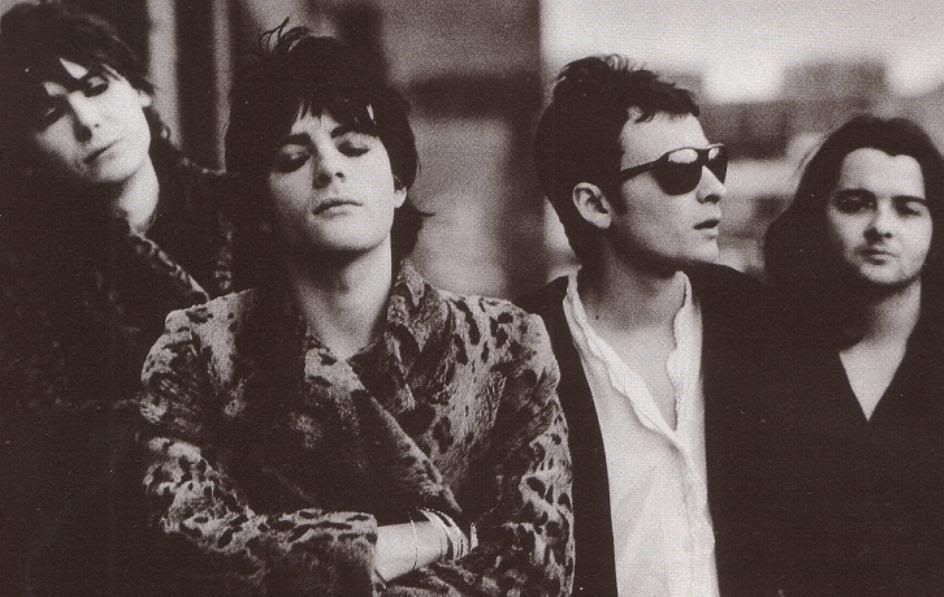

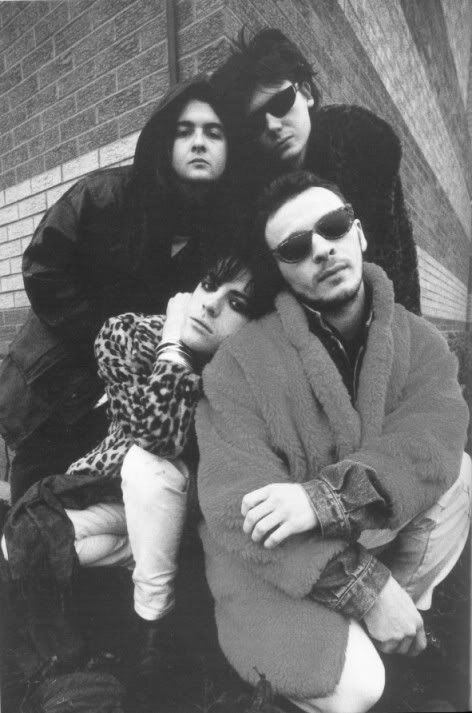

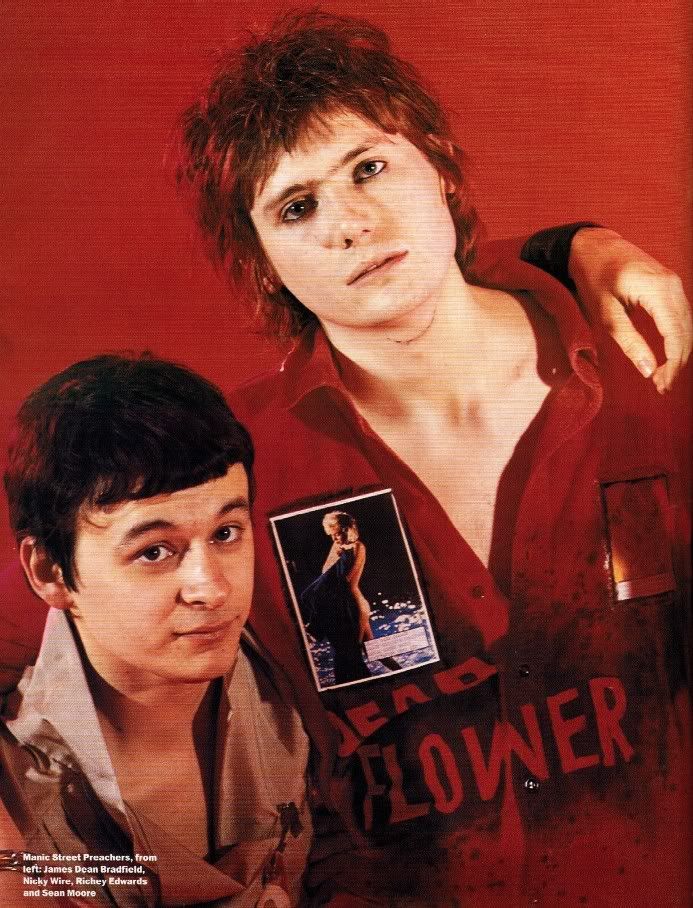

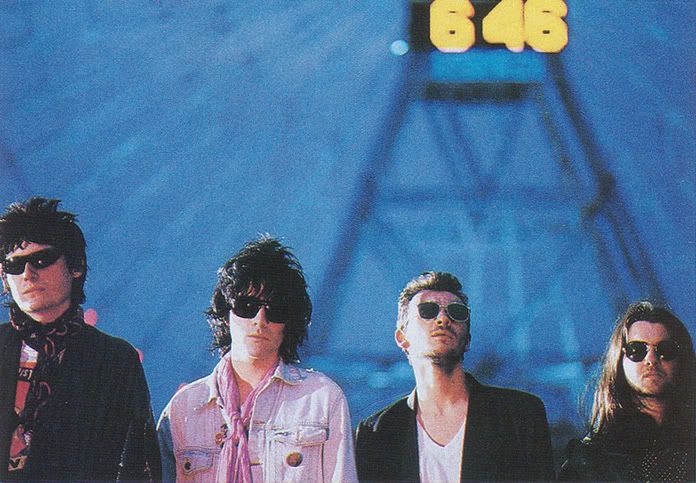

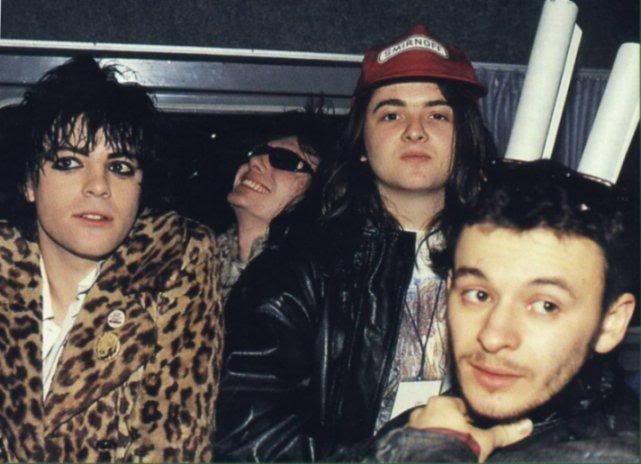

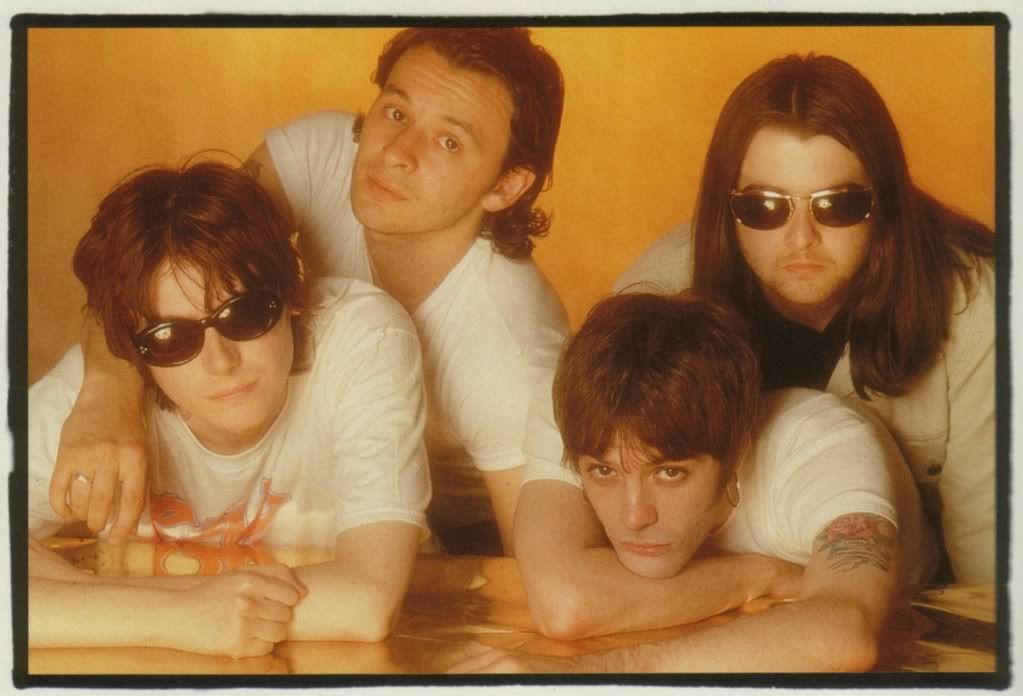

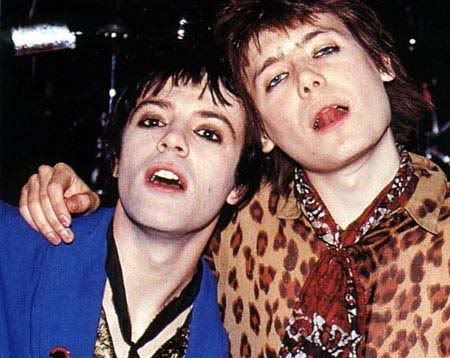

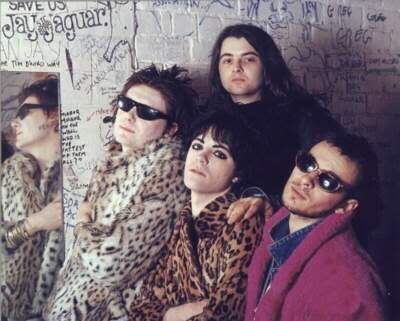

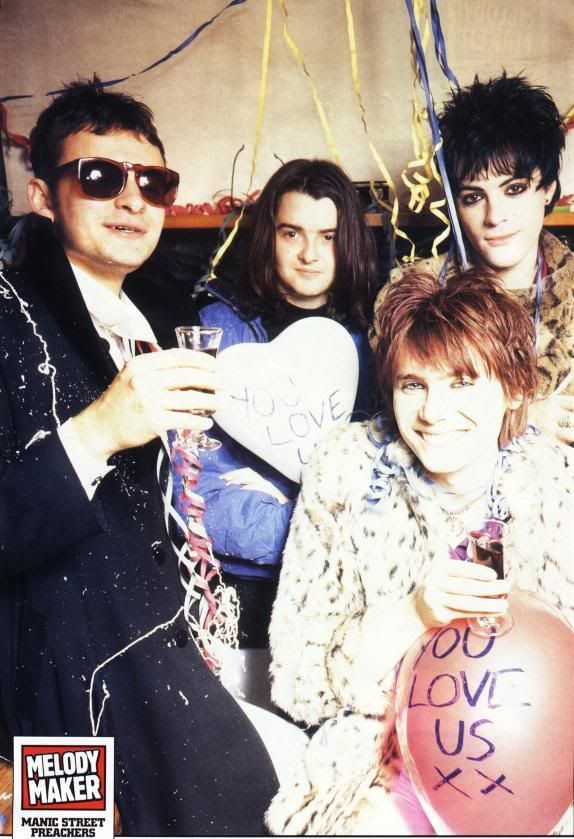

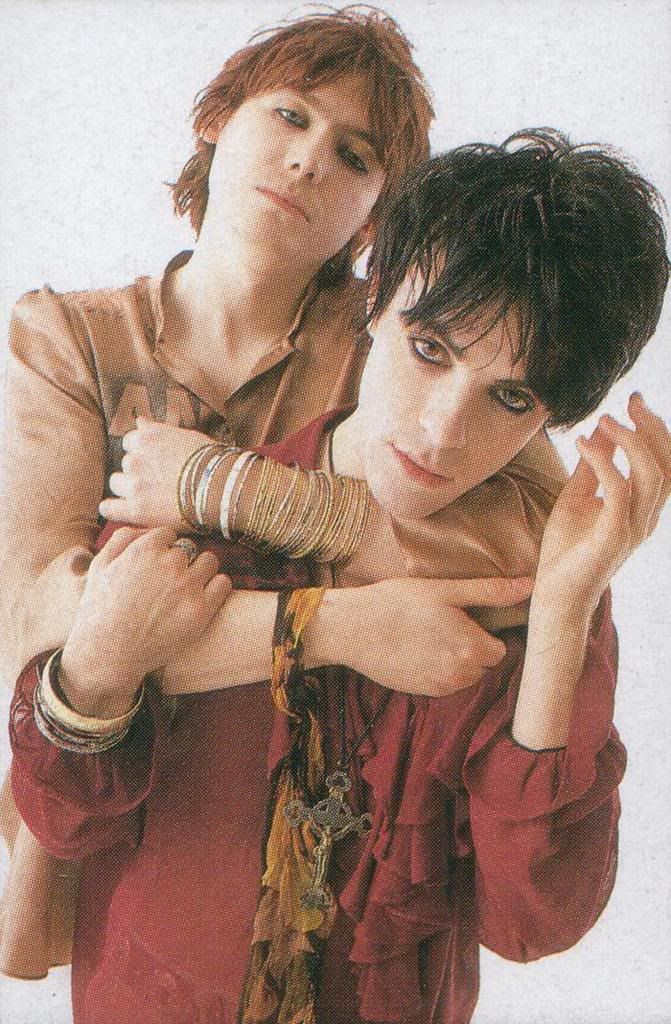

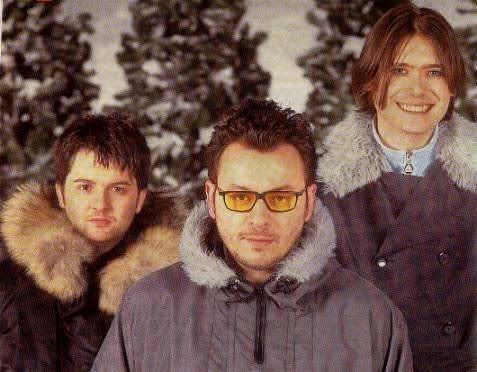

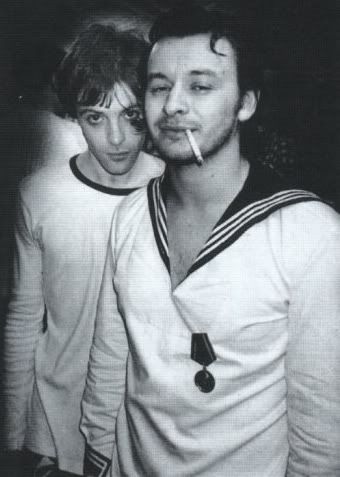

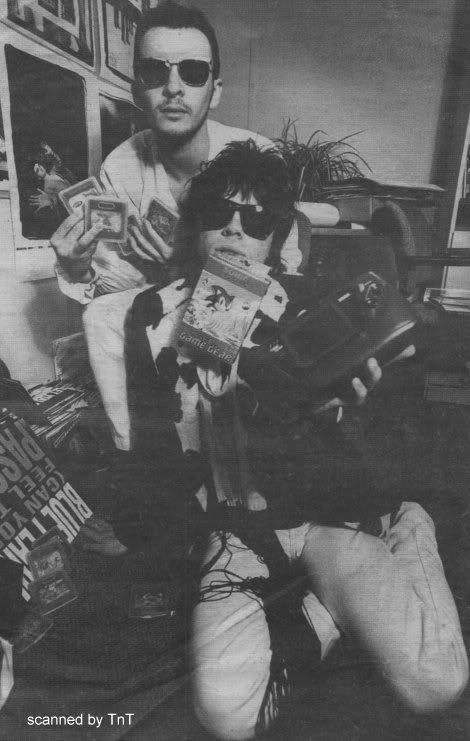

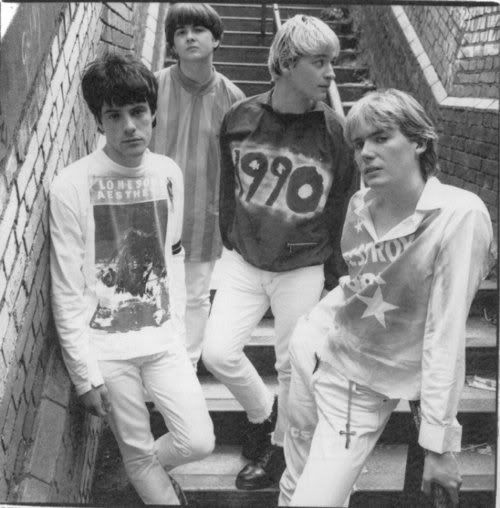

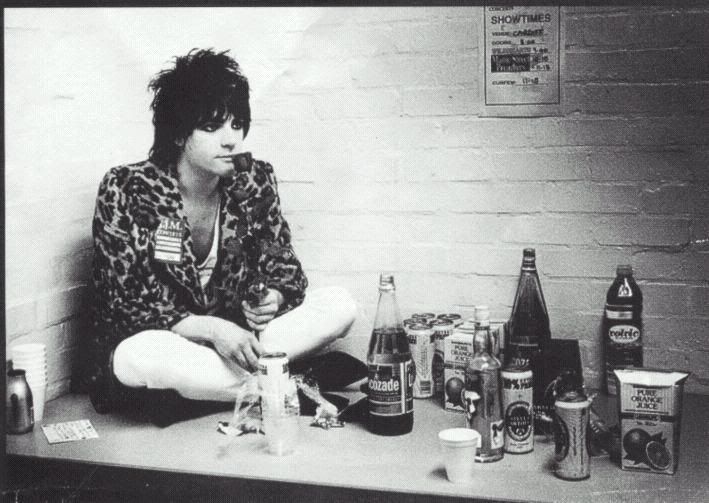

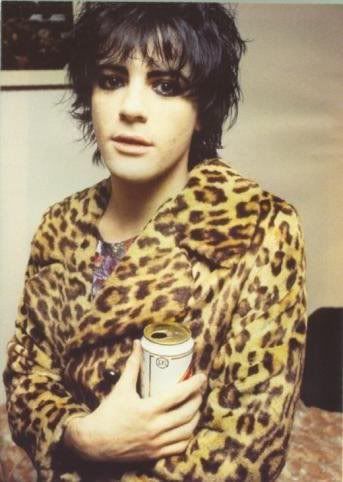

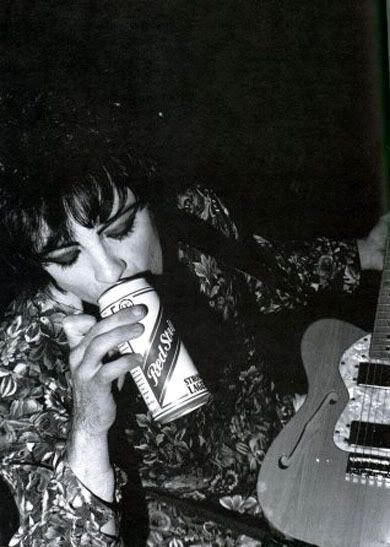

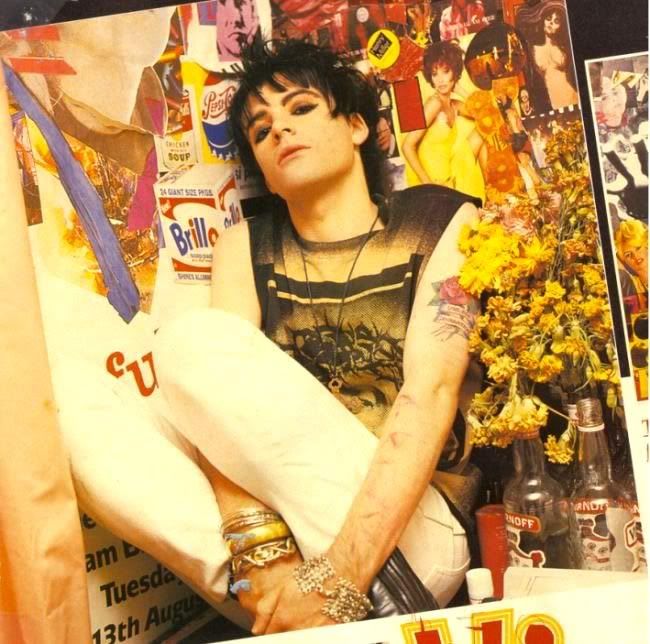

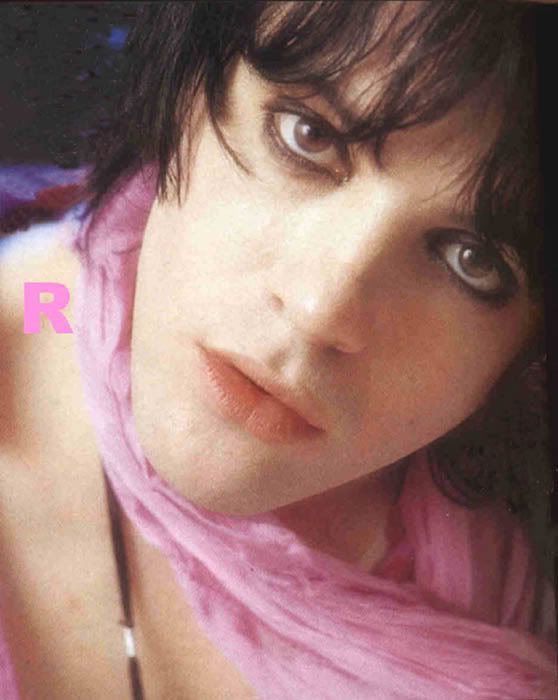

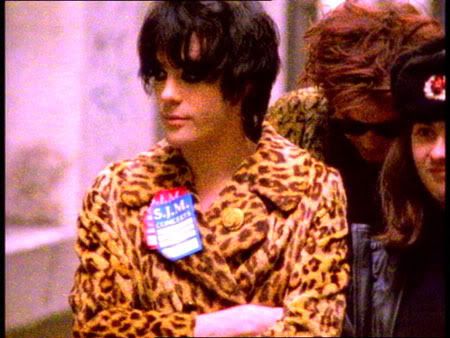

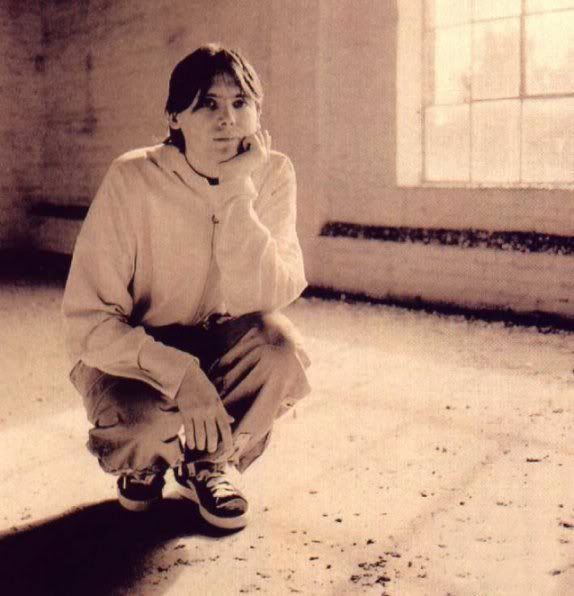

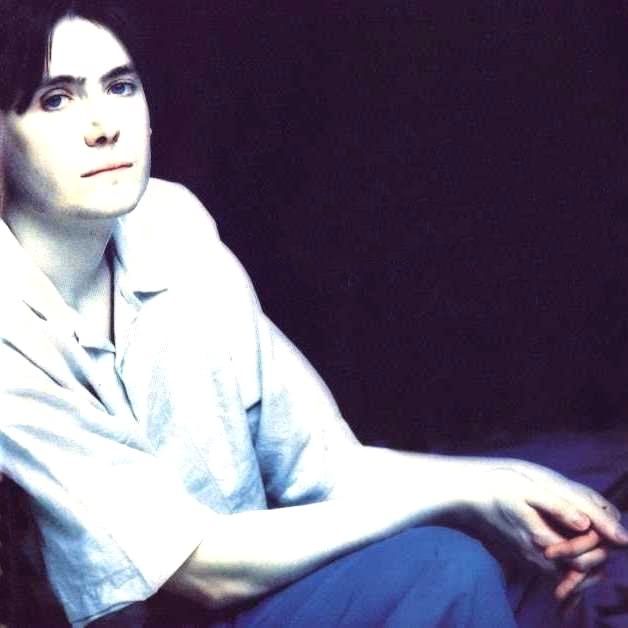

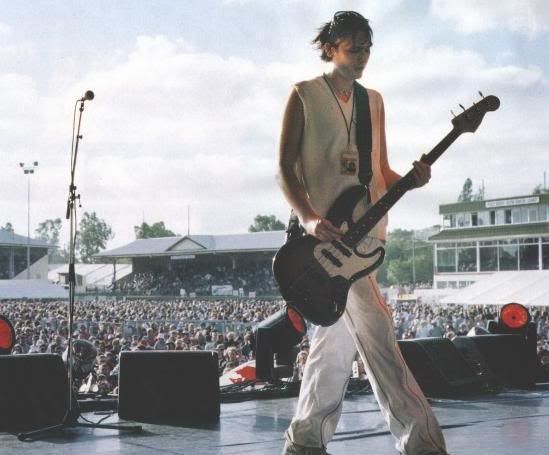

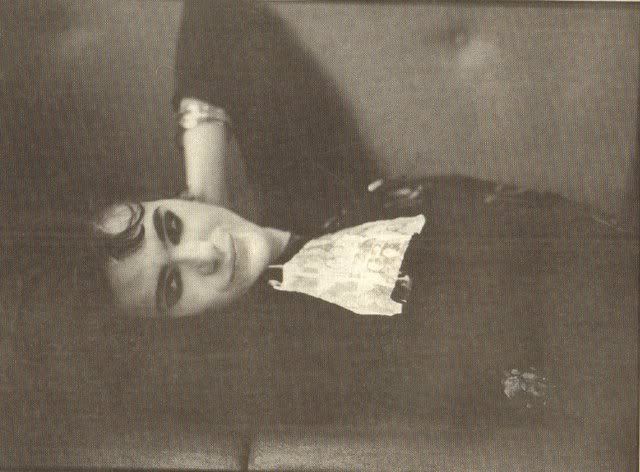

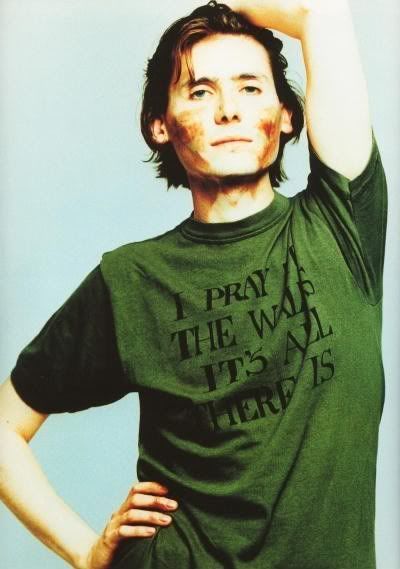

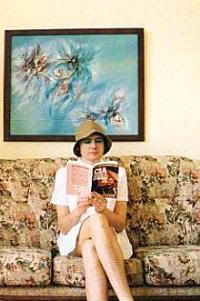

RICHEY JAMES EDWARDS

Richey Edwards

"I wanna sing about a culture that says nothing. I wanna say the fact that basically all your life you're treated like a nobody."

Born: 22 December 1967

Role: Lyrics, rhythm guitar

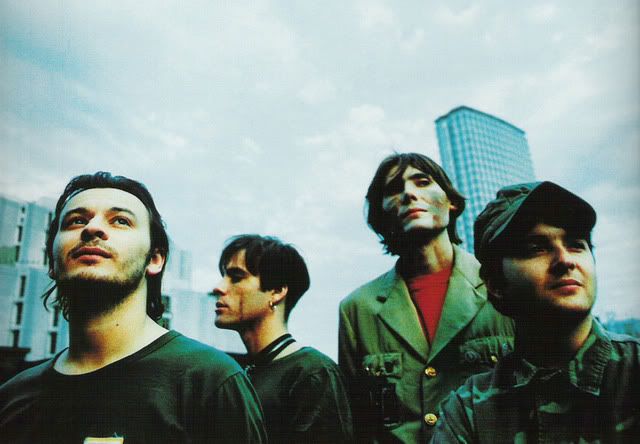

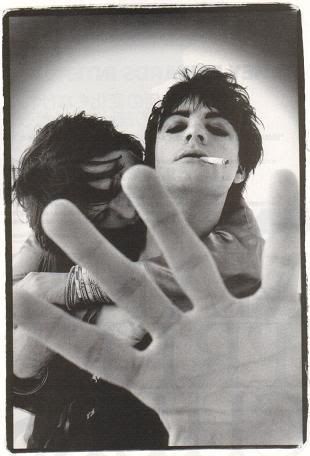

The disappearance of Richey Edwards - co-lyricist, rhythm guitarist and scar-bearing ideologue of the Manic Street Preachers - has become one of the great modern musical legends of our times.

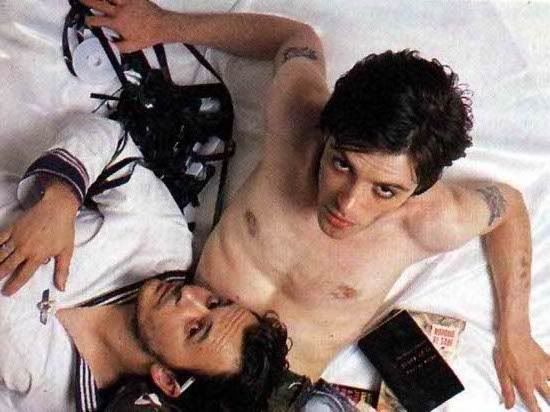

It's not difficult to see why Richey became such a powerful icon for the Manics' eyeliner-clad devotees: through his very public battles with alcoholism, anorexia, and self-mutilation, Edwards became a spokesman for issues previously considered taboo - a lightning rod for the marginalised, alienated, and dispossessed.

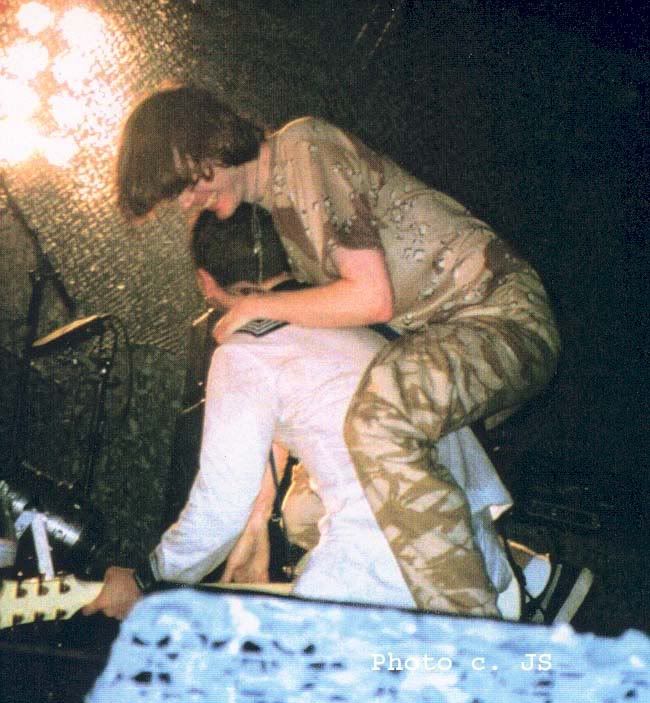

He even spawned a slogan, '4Real' - a grim reference to an incident dating back to a gig at Norwich Arts Centre in the May of 1991 where, challenged by then-NME journalist Steve Lamacq to prove the weight of his conviction, he carved the term into his arm with a razor.

"When I cut myself I feel so much better," said Richey of his habit. "All the little things that might have been annoying me suddenly seem so trivial because I'm concentrating on the pain. I'm not a person who can scream and shout so this is my only outlet. It's all done very logically."

Born in Blackwood to Sheryl and Graham Edwards, a pair of devout Methodists that ran a hairdresser's on Blackwood High Street, Richey was a quiet, acne-ridden kid - the stereotypical teenage misfit.

Turned off by the didactic learning of the classroom, he pursued his own education, the books of George Orwell, Albert Camus, Sylvia Plath, and Brett Easton Ellis forming a self-styled reading list. He adored Echo And The Bunnymen and Public Enemy, but by the time the other Manics were tentatively learning chords, he was ensconced in Swansea University on a political science degree.

The company of a rowdy mass of young humanity was not a pleasant experience for Edwards. "It was full of people who wanted to sit around and do as little as possible, other than have as much fun as they could. But I never equated university with fun. I thought it was about reading and learning."

But Richey soon became invaluable to the Manics. As van driver he ferried the band to and from shows, as the band's 'Minister of Information', he mailed bile-filled press releases to the London music inkies. It was only a matter of time before he picked up a guitar and became the Manics' fourth member.

Sadly, despite some intensive lessons from James, his poses were more practised than the actual music. "Why is everyone hung up on an ugly piece of wood and metal and strings?" he asked. "I can't play guitar very well, but I wanna make the guitar look lethal."

Where Richey did excel, however, was in the field of lyric-writing. Seldom without his notebook, he was a prolific ideas man, penning reams of verbose, ennui-laden tracts on prostitution, capital punishment, and the Holocaust - themes that featured heavily on the Manics' third album, the harrowing The Holy Bible.

Such bleak topics spoke volumes about Richey's fragile state of mind. By the May 1993, his anorexia and alcoholism had reached such an extreme level that he required professional help. The guitarist spent much of the summer institutionalised in an effort to kick his psychoses, bouncing from an NHS ward in Wales to celeb-friendly detox haunt The Priory.

Nevertheless, Edwards was quick to insist that he would never put his life in danger. "In terms of the s-word," he explained, "That does not enter my mind. And it never has done, in terms of an attempt. Because I am stronger than that."

Although the details of Richey's disappearance on the eve of an American tour have been well-documented, there remain few concrete facts and fewer leads. A handful of things are clear. The guitarist left London's Embassy Hotel at 7am on the morning of 1 February 1995. He visited his home in Cardiff, where he left his passport, credit card, and Prozac. He drove his Vauxhall Cavalier to Aust motorway services by the Severn Bridge, where it was discovered with a flat battery on 17 February.

And then, nothing. A number of reported sightings remained unconfirmed. A mountain of macabre newspaper speculation turned up no clues. It was as if Richey had simply disappeared off the face of the earth.

Is Richey dead? It's impossible to say. After seven years the family of a missing person are entitled to have the person declared dead and apply for his estate, but a statement issued by Sony in early 2003 said otherwise. "For the family of Richey Edwards and the members of the Manic Street Preachers nothing has changed," it read. The police file remains open, and the remaining band members continue to pay royalties into a bank account for him.

Autor: Manic Street Preachers o 11:57 0 komentarze

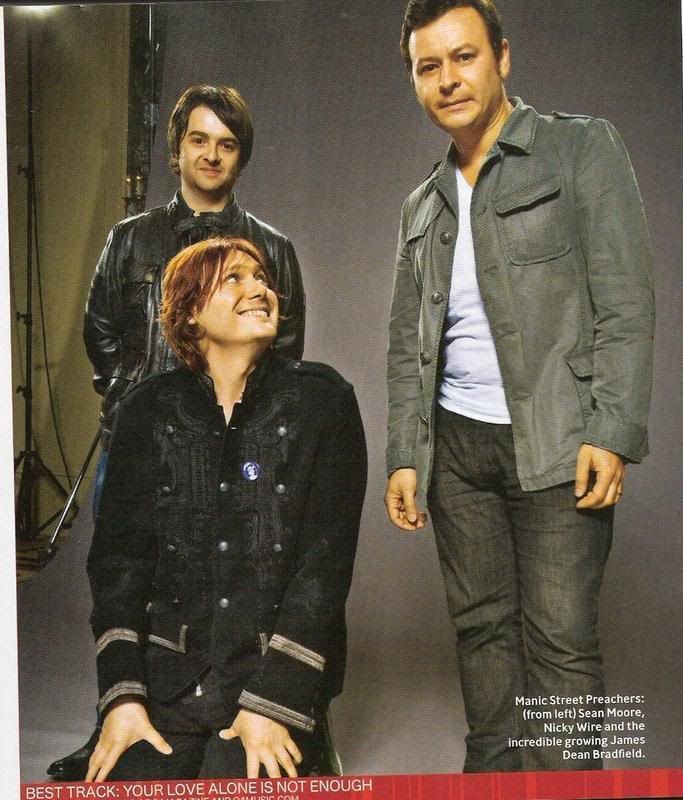

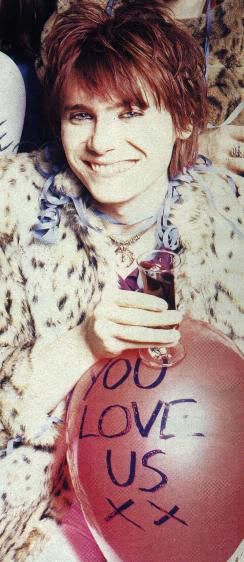

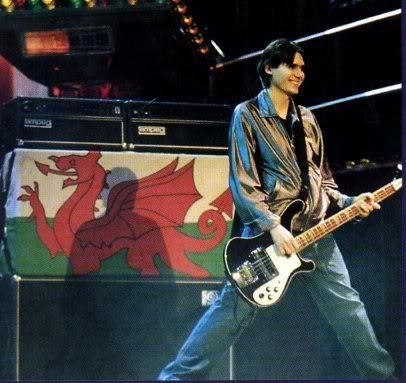

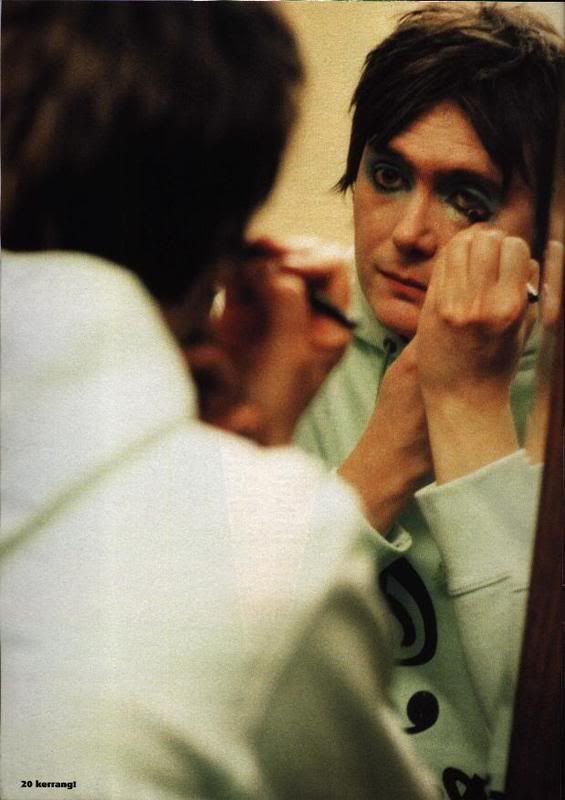

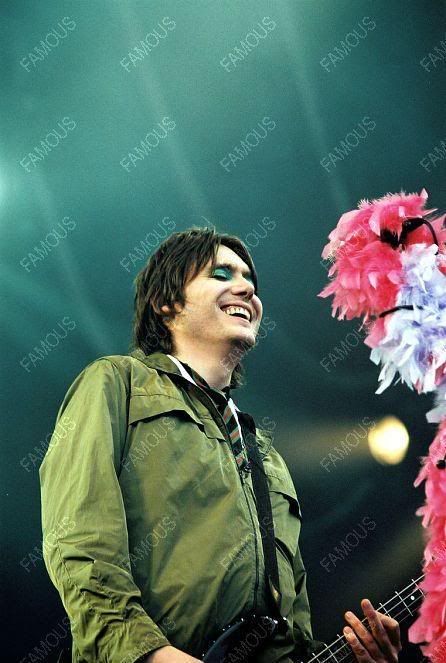

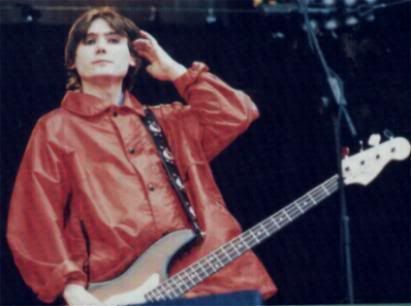

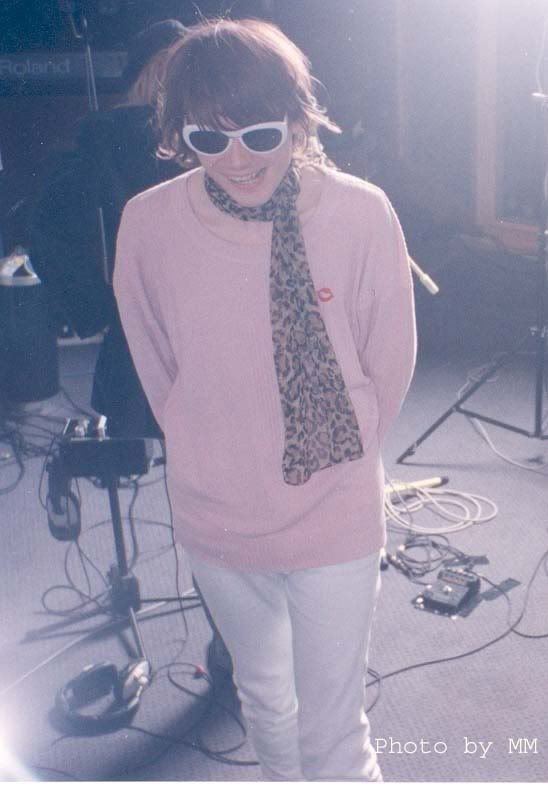

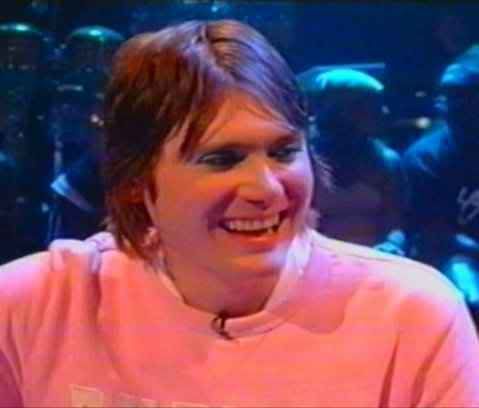

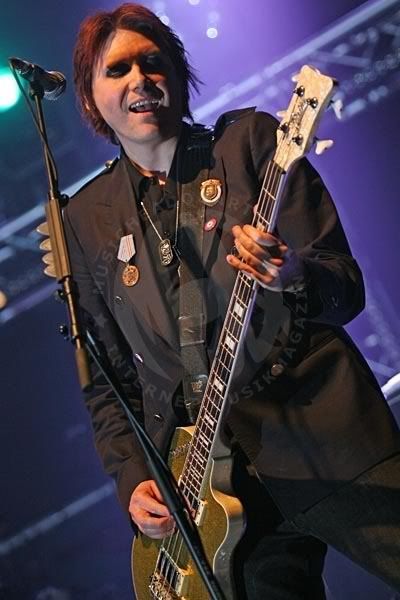

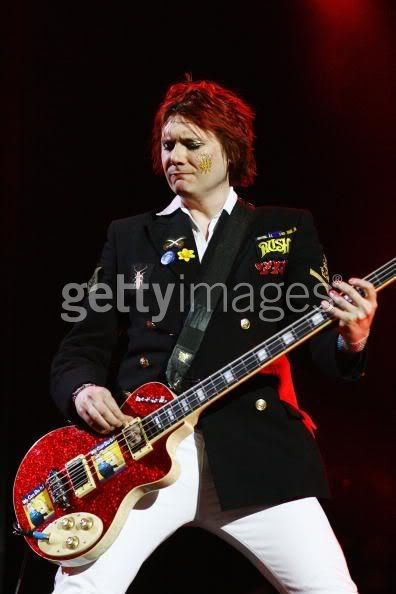

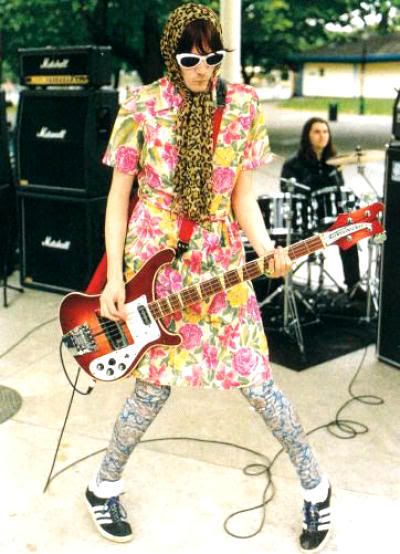

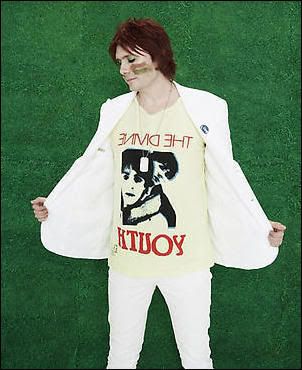

NICKY WIRE

Nicky Wire

"We are total prostitutes. Sluts! If we can get across what we really feel, that's more important than any credibility."

Born: 20 January 1969

Role: Bass, lyrics, backing vocals

The towering, bass-wielding motormouth with a taste for controversy and a fetish for wearing women's frocks, Nicky Wire is a ball of contradictions.

On one hand, Wire - named in honour of his lofty frame - is Wales' most celebrated glamourpuss punk-rocker, throwing mighty scissor-kicks and slaying sacred cows with every lash of his sharp tongue. Yet offstage, Nicky is a teetotal homebody with a cleanliness regime that borders on the obsessive-compulsive and - count 'em - three Dyson vacuum cleaners.

Born in the rundown former mining town of Blackwood, and brought up a mere 200 yards from Richey Edwards, Nicky was a gangly boy who excelled at sports, especially football - indeed, he even received a trial for Arsenal football club, although a bad back put pay to any dreams of a career at Highbury.

Nicky, however, was also a voracious reader and writer. "By the time I was 16 I'd read and studied the complete works of Philip Larkin, Shakespeare, all the Beat generation, every film," explains Nicky.

Marxism was another formative passion, the result of growing up in an area still defined by the radical politics thrown up by the Miners' strike of the mid-'80s. Elder brother Patrick Jones was also an influence, his hand-written volumes of verse about life in post-industrial Wales an inspiration to the young Wire and his early lyrics.

Always one for running off at the mouth, Wire has landed the band in hot water on countless occasions. Few can forget the time he told a Glastonbury crowd, "Somebody ought to build a bypass over this shithole," or wished death-by-Aids on REM singer Michael Stipe.

Indeed, sometimes his quick tongue has overwhelmed his good sense: at a gig in Bangkok, where the security guards wielded electric batons and the penalty for treason is death, Nicky dedicated a furious rendition of Repeat to the Thai monarchy. Manics biographer Simon Price attests that Nicky spent a sleepless night worrying if he was going to be clapped in chains by the Bangkok secret police.

One of Nicky's most glaring contradictions is his attitude to Welsh identity. When asked, in the early days, if he felt European, British, or Welsh, he responded like a man that recognized no borders: "Nothing. I wish we could feel something - maybe we'd be more rounded people. We've always been too alienated."

Yet by 1996, Nicky's feelings towards the land of his fathers had mellowed. Live shows saw him play with a Welsh flag draped over his amp, and on Ready For Drowning - a song from 1998's This Is My Truth - he paid lyrical tribute to Welsh heroes like Dylan Thomas and Richard Burton. When asked by a journalist what his favourite journey was, his answer spoke volumes. "Coming home over the Severn Bridge," he replied.

Nicky does admit a few vices. He used to be addicted to fruit machines - "I had a three grand overdraft at university because we'd put £50 worth of tokens in to try and win £4 worth of tokens for a meal," he explains - and he's an avid viewer of every sports channel on the box.

Perhaps it makes perfect sense, then, that this very sedentary revolutionary is married to his childhood sweetheart, Rachel, who he met when he was 16. They live together in a house in Blackwood, a town Wire reckons he will never leave.

"I could be happy in these four walls for the rest of my life," he confirms. "I'd be happy if I never left Wales again. It might seem like a prison to some people, but the prison I've put myself in makes me feel happy."

Autor: Manic Street Preachers o 11:56 0 komentarze